|

In an attempt to scale-up the success of early trials, Upstream Allies are now engaged in a large, replicated experiment to restore river prawns and follow their benefits for human disease in Senegal. The big study began in spring 2016, with more than 1400 children, and 1500 snails among 16 villages tested (and the children treated) for schistosomiasis between February and May. Baseline studies at all 16 villages without prawns will continue through this year until prawns are delivered to a subset of the villages next year (scheduled for spring or summer 2017). Reinfection with schistosomiasis will then be analyzed at follow up visits to measure whether prawns can deliver the service of reducing snails and schistosomiasis transmission across a diverse set of villages and ecosystems in the Senegal River Basin.

Human testing and treatment: 16 villages were recruited to the study following many months of preliminary research and dialogue with the village chiefs, parents, teachers, and other leaders. This spring, 1480 children were tested and treated for schistosomiasis, after they and their families provided informed consent to participate in the study. This marks the official launch of the baseline studies for our "proof of concept" trial, aimed to test whether prawns can deliver public health benefits in the form of reduced schistosomiasis transmission across a large and replicated study population. Schistosomiasis is a grave problem for these communities, with S. haematobium prevalences ranging from 42 to 99% in the children in our study, and S. mansoni prevalences ranging from 0 to 97%. After having provided all of the children who participated with praziquantel to clear their infections, our team will return again next year. Ecological research: At each village, people use anywhere from one to four water access points, which are places along the shorelines of rivers, streams, lakes, and canals where vegetation has been cleared to make access for daily water needs such as washing dishes, bathing, washing animals, swimming, access for fishermen, and water play for children, among other activities. It is at these water access points that people are routinely exposed to schistosome parasites, emitted from aquatic snails. This spring, we started to collect detailed ecological information on the abundance and distribution of aquatic snails, birds, and plants at all 33 water points among the 16 recruited villages. Environmental sampling will continue regularly, throughout the seasons, to piece together the ecology of schistosome parasites and other organisms in these environments. Socio-economic studies: Every village has a unique set of circumstances with regard to the residents' diverse employment and various livelihoods, access to healthcare, attitudes towards the environment, socio-economic status, and cultural and educational backgrounds. These socio-economic factors may play a role in the disease risks each villager faces and the potential success of any intervention. That is why, beginning this fall 2016, we are launching a socio-economic study at our 16 villages. The study starts with qualitative interviews of village leaders (underway) and will be followed by focus groups to map water access points inside and outside the villages, along with in-depth questionnaires to identify key socio-economic drivers of health and disease risk.

0 Comments

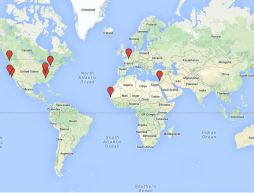

Construction of the Upstream Alliance prawn hatchery is now complete! The hatchery is located on the campus of the Gaston Berger University in St. Louis Senegal. The electricity to the beautiful new building was connected in early July. The building is ready to receive the tanks, blowers, plumbing, etc. which are en route from the U.S., with the installation and initial operations expected to be complete by October 2016. The outcome of the most recent rearing of brood stock in large ponds has been positive. This means that the adult Macrobrachium broodstock for the new hatchery will be available from the start of operations (>3000 broodstock). The permission to work on four other growout ponds has been secured with our partner organization ANIDA in Senegal, based on the positive results from fish and prawns trials that have been ongoing. This additional capacity will allow us to work with various prawn stages (and/or with two prawn species) simultaneously. Click to download the kmz file - open it in Google Earth and fly over the 16 villages in Senegal!

Phase II is set to begin

In the first phase of research, scientists at The Upstream Alliance tested whether prawns would eat snails in the laboratory. Then they tested whether prawns would eat snails in the wild, at a single water access site in Senegal. The answer on both occasions was a resounding: yes. The challenge now is to follow up on these promising Phase I results (published in the journal PNAS), and begin Phase II: a replicated experiment. A newly launched effort to scale up the intervention has required the objective evaluation of 700+ villages in Northern Senegal. The process has just been completed, and scientists and stakeholders have selected 16 villages for Phase II of the study, to begin February 2016. An objective site selection process The selection process of villages was based on a list of 695 villages in the lower Senegal River Basin, located less than 10km from a water source, obtained from l’Agence Régionale de Dévelopement, Senegal. The list was supplemented with 9 villages encountered in the field that were not included in the base list, leading to a total of 704 villages to be evaluated. The selection process included five large steps; geographical exclusion, preliminary google earth evaluation, a first field visit, and a second, and third field visit. Villages were selected based on the presence of a minimum of one, and maximum of four, regularly used water-access points along the lake, river, or irrigation canals, so that water access from the village was “enclosable” with net pens (to contain prawns for the experiments). The water access points were selected to be permanent (not temporary) freshwater (not brackish) ecologically in place for a couple of months at least, so no recent large disturbance such as dredging. Only rural villages which share a more common lifestyle pattern and typically represent the highest risk sites for schistosomiasis transmission have been selected. To achieve this, villages were excluded if they were too large (top 10th percentile, considered urban) or too small (bottom 10th percentile) to be comparable. Many villages were excluded based on the additional objective criteria, such as: lack of a school, too poor water quality to support prawn restoration, or too little local schistosomiasis transmission in baseline questionnaires. This is an important step forward "Site selection represents a key step towards expanding the research, and testing whether prawn reintroduction can deliver on its promise of schistosomiasis reduction at many replicated sites," says Upstream Ally Susanne Sokolow. The team is excited for the next challenge of recruiting village children and parents to voluntarily take part in the study and sourcing thousands of prawns for the upcoming intervention. Prawns preferentially attack schistosome-infected snails

A new laboratory study published in the Journal of Experimental Biology provides insight into the impacts of parasitic infection on predator–prey dynamics. In aquaria, freshwater prawns preferentially attacked infected snails, with an attack rate 25% higher than seen for uninfected snails. Why? The answer is unclear, but this new research by Upstream Alliance scientists demonstrates that the infected snails have a sluggish response to predatory threats. "In [snail] behavior trials, infected snails moved less quickly and less often than uninfected snails, and were less likely to avoid predation by exiting the water or hiding under substrate," say the authors. The changes in snail behavior could be the result of deliberate manipulation on the part of the parasite (to keep snail hosts in the most beneficial position for the parasite, despite predation risks) or a side effect of infection. Either way, these results support the idea that boosting natural rates of snail predation using freshwater prawns may be a useful strategy for reducing transmission in schistosomiasis hotspots. Sign up for the Upstream Alliance email list to stay up-to-date on project developments and news. Follow Upstream Alliance on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook. Reference: Swartz, S.J., DeLeo, G.A., Wood, C.L., Sokolow, S.H. 2015. Infection with schistosome parasites in snails leads to increased predation by prawns: implications for human schistosomiasis control. Journal of Experimental Biology. [Download PDF] or link to online article Press coverage: Schistosome parasite alters snail behaviour Kathryn Knight, J Exp Biol, 2015 Contact Us: The Upstream Alliance, [email protected] Susanne Sokolow, [email protected] Prawns Mean Business: Leveraging Aquaculture to Reduce a Disease of Poverty

The escape from schistosomiasis, a poverty-inducing infectious disease, may come in the form of an African freshwater prawn, a source of sustainable disease control and aquaculture revenue. Schistosomiasis doesn’t just kill – it traps. People living in poverty are more likely to contract the disease, which is caused by parasitic, water-borne flatworms. What’s more, the debilitating symptoms of infection can prevent people from working, thus creating a disease-poverty cycle. An Ecological Solution Research conducted by The Upstream Alliance, a global partnership of scientists specializing in disease ecology, health, aquaculture and development, indicates that the African river prawn could biologically control the parasite. In the scientific paper, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers studied two villages – both situated by the Senegal River, and both heavily affected by schistosomiasis. In one village, researchers stocked prawns in a water access point, and in the other village, they just observed the site. Over 18 months, they found that the first village experienced an 80% lower abundance of infected snails and a 50% reduction in the intensity of human schistosomiasis infections, measured as the number of flatworm eggs in a person’s urine or stool. “The results of our study open the pathway to a novel approach for the control of schistosomasis,” said Stanford professor of ecology Giulio de Leo. Why? Prawns are voracious predators of snails, which host schistosoma parasites before they enter humans. Prawns cannot become infected when they eat the snails, so more prawns means fewer parasite-carrying snails and fewer parasites in the water to infect people. A Business Opportunity Freshwater prawns are considered a delicacy, so the prawn business is more than a global health solution – it’s also a business opportunity. Senegalese fishermen have fished for prawns for centuries. But, in Senegal, the prawn population has hit a concrete wall – literally. The Diama Dam, constructed in 1986, blocked the downriver migration of prawns to breeding spots at the mouth of the Senegal River. More than that – the dam increased the aquatic vegetation along the river that schistosoma-hosting snails love. In such a favorable environment, and without an important predator, snail populations exploded. Schistosomiasis prevalence followed suit. Removing the Diama Dam is not an option. The dam sustains agriculture in Senegal and provides fresh water to hundreds of thousands of individuals. Luckily, there are other ways to help sustain a healthy prawn population, such as constructing a fish ladder. Yet another is prawn aquaculture – a viable and crucial alternative for the Senegalese. Initiatives such as Aquaculture Pour La Santé, a subsidiary of Biomedical Research Institute Espoir Pour La Santé (EPLS, the major Senegalese partner of The Upstream Alliance) are exploring opportunities to stock prawns in parasite-infested hotspots in the Senegal River Basin. This opportunity could open up a new realm of entrepreneurship and enhance food security in underdeveloped areas. EPLS CEO Dr. Gilles Riveau says, “It still needs a lot of brain storming, a lot of research, a lot of work to achieve a balanced, effective, and highly reproducible application of this strategy.” But, he says, prawns can create a “constant effect” on the reduction of schistosomiasis transmission in a sustainable way[GR1] . Connecting Research to Action Current efforts to control schistosomiasis in Senegal include large campaigns using the drug praziquantel, which kills schistosomiasis after people have become infected. Upstream Alliance researchers show that adding prawns to the mix through a two-pronged campaign could defeat the parasite in two stages of their life cycle: prawns clear parasites from the environment and drugs clear parasites from the people. “Our research shows that combining mass drug administration campaigns with snail predators could have a lasting effect on public health,” said Susanne Sokolow, the study’s lead author. Next steps for the project are currently under way within The Upstream Alliance. Plans include introducing prawns to more village water access points, researching a prawn passage on the Diama Dam, and exploring new technologies and markets for African prawn aquaculture. Riveau says, “Much of the scientific field work will take place in the low valley of Senegal river through EPLS Center, including selection of villages, medical and parasitological follow-up, [snail studies, and] prawn production [GR2] and stocking.” Sign up for the Upstream Alliance email list to stay up-to-date on project developments and news. Follow Upstream Alliance on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook. Reference: Sokolow, Huttinger, Jouanard, Hseih, Lafferty, Kuris, Riveau, Senghor, Thiam, N’Diaya, Faye & de Leo. 2015. Reduced transmission of the human schistosomiasis after restoration of a native river prawn that preys on the snail intermediate host. PNAS. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1502651112 Contact Us: The Upstream Alliance, [email protected] Gilles Riveau, Biomedical Research Institute Espoir Pour la Santé, [email protected] Nicolas Jouanard, Biomedical Research Institute Espoir Pour la Santé, [email protected] Prawns. What are they good for? An article released by the University of California in Santa Barbara, written by Sonia Fernandez, argues that prawns – particularly African freshwater prawns – carry benefits far larger than their size would suggest: they may fight disease.

Researchers of The Upstream Alliance suspect the prawns play a role in controlling schistosomiasis, a chronic, waterborne disease caused by a parasitic flatworm. Schistosome parasites are transmitted through aquatic snails, an intermediate host, before infecting humans. Here’s where prawns come in: prawns prey on these snails, without becoming infected themselves. So, in an undisturbed ecosystem, prawns exert some control on schistosomiasis. The prawns grow larger than the shrimp you would find in the supermarket, but smaller than a lobster. Tan in color, with long, blue-tipped claws, the prawn is rich in protein and iron. Prawns can be a vital source of nourishment in impoverished sub-Saharan Africa. What’s more, The Upstream Alliance wants to use prawns’ inherent predatory nature to “devise the optimal win-win-win-win solution that benefits human health, environmental restoration, hunger alleviation and economic development,” said Susanne Sokolow, a researcher at Stanford University and UC Santa Barbara and co-director of The Upstream Alliance. When the schistosome parasite infects humans, it lays up to 3,000 eggs a day, hoping that those eggs will leave the body through feces or urine and make their way to the waterways. Instead up to half the eggs stay in the body to create adverse side effects. Schistosomiasis leads to poor physical health, an impaired immune system and cognitive difficulty. Schistosomiasis can be deadly but it does not always kill; it leaves its victims feeling weak and ill. In many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, dams, irrigation, or other manmade constructions disturb river ecosystems. The Diama Dam in Senegal demonstrates this clearly. The dam blocks the migration of river prawns, so few prawns are found upriver of the dam. Sure enough, without prawns to keep snail numbers low, schistosomiasis prevalence exploded after the construction of the Diama Dam. Removing the dam isn’t an option, so researchers are looking for other ways to reintroduce prawns to the Senegal River. Stocking aquaculture-raised prawns in Senegal will, Sokolow hopes, control disease, create a source of food, restore the biodiversity lost by the dam, and generate economic revenue for local people. The potential solution has caught outside attention. The National Science Foundation awarded $1.5 million to a team of researchers and scientists partnered through The Upstream Alliance. Members include Sokolow from Stanford, Armand Kuris and David Lopez-Carr from UC Santa Barbara, James Tidwell of Kentucky State University, and James Sanchirico of UC Davis. The Upstream Alliance has also received funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Grand Challenges Canada. Upstream will use their new resources to establish more prawn stocking sites to further assess the benefits of the crustaceans on disease, health, and economics. The researchers plan to take a multipronged approach that will include drug treatments and reintroduction of the prawns, surveys, monitoring, interviews and experiments that are expected to provide insights across various fields, including ecology, epidemiology, aquaculture, economics and other social sciences as well as mathematical modeling. Check back often to track our progress. Aquaculture for the native African prawn Macrobrachium vollenhovenii has never been tried at a commercial scale. But this technology development is critical to bring back the prawns to the upper reaches of the Senegal River, after they were excluded by the Diama Dam in 1986. After they were excluded, snail populations climbed, leading to outbreaks of schistosomiasis, a parasite carried by the tiny snails. By consuming schistosomiasis-infected snails in the environment and lowering the parasite's transmission to people, prawns are a natural and safe way to fight the disease. Senegalese entrepreneurs, scientists, and aquaculture specialists are eager to bring the latest prawn-rearing technology to Senegal and put prawns back on the table, literally. During May 2015, the Upstream Alliance kicked off the development of a prawn hatchery business plan in Senegal. Upstream Alliance aquaculture and ecology experts joined forces with Espoir Pour La Sante (EPLS) team-members in Senegal to site the future prawn hatchery. The team visited the Diama Dam, and attended one of the government's ongoing praziquantel drug administration programs, led by EPLS, in a local school. Upstream Alliance ecologists and malacologists also started to test field protocols to accurately assess snail numbers and measure their parasite prevalence. Partners from across four continents converged in Monterey, CA January 28-30 2015 to discuss research and milestones for the prawn-farming enterprise for schistosomiasis reduction in Senegal West Africa. Old friendships were rekindled and new ones were forged and The Upstream Alliance was born. After two days of presentations by experts, break-out sessions, and intense scientific and strategic discussions, the participants joined the faculty and students from Stanford University, the meeting's hosting institution, for a magical dinner at the Monterey Bay Aquarium to commemorate the event. |

The Upstream Alliance News and EventsNews feed about the activities, news, and events of The Upstream Alliance: Partners in Schistosomiasis Reduction Archives

August 2016

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed